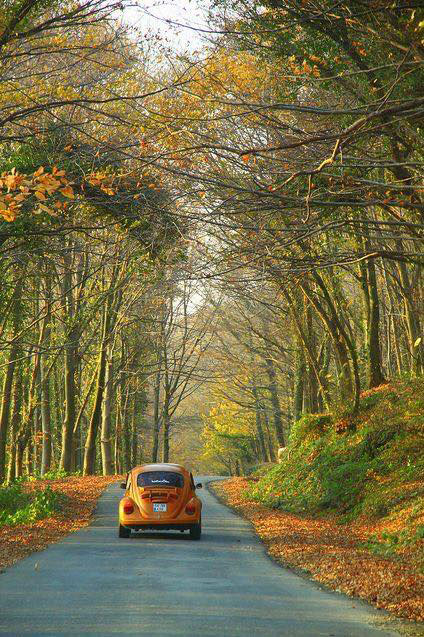

I love the back roads. I much prefer them to the big highways and especially the interstates. They are more pleasant, less stressful, more scenic for the most part and many times, it takes about the same time to get from Point A to Point B as it takes using the big roads. Driving in Atlanta is an absolute nightmare, as anyone who lives here knows. The interstates outside of the city are just as bad, I-75 through Henry County in particular. I don’t know the reason, but it is backed up in both directions day in and day out from Stockbridge to Locust Grove. Things usually back up again around Macon, where it seems like they have been working on the road for the last thirty-five years or so.

I love the back roads. I much prefer them to the big highways and especially the interstates. They are more pleasant, less stressful, more scenic for the most part and many times, it takes about the same time to get from Point A to Point B as it takes using the big roads. Driving in Atlanta is an absolute nightmare, as anyone who lives here knows. The interstates outside of the city are just as bad, I-75 through Henry County in particular. I don’t know the reason, but it is backed up in both directions day in and day out from Stockbridge to Locust Grove. Things usually back up again around Macon, where it seems like they have been working on the road for the last thirty-five years or so.

For these reasons, I avoid I-75 South like the plague. One of my favorite back roads is Ga. Highway 212. Its northern terminus is in south DeKalb county and the southern end is in Milledgeville. The road winds through Klondike, Conyers, across Jackson Lake, and through Monticello before terminating in Milledgeville. The stretch between Monticello and Milledgeville is my favorite, with rolling hills, large farms and beautiful scenery. Recently, Jackie and I took a trip to Fernandina Beach. We took 212 from Conyers all the way to Milledgeville, picked up U.S. 441 through Dublin to McRae and then went out U.S. 341, aka The Golden Isles Parkway to Brunswick, where we got on I-95 South. While we were on 441 heading toward Dublin, Jackie said, “Are we in The Twilight Zone? There’s no traffic. Where is the traffic?” “Probably on 75 South,” I answered. A little while later, I looked to the right and pointed. “There’s something you don’t see every day,” I said. On the side of the road were three wild boars, upright and feeding. A few miles down the road there were three more. You never know what you might see on the back roads.

There are really only two towns on The Golden Isles Parkway between McRae and Brunswick and those are Baxley and Jesup. The rest are pretty much little wide spots in the road where the speed limit will suddenly drop from 65 to 35 and you have to be careful because Barney might be behind a bush on his motorcycle with the sidecar, wearing his helmet, goggles, gloves and scarf.

Another of my favorites is Ga. Highway 42. Highway 42 begins in Byron and end at its northern terminus in Brookhaven, a suburb of Atlanta. It sort of has a special place in my heart for several reasons. First, it runs concurrently with U.S. 23 through East Atlanta, where I was born. This stretch of road is known as Moreland Avenue, which the road is known as from Conley Rd. to Ponce de Leon Ave, after which it becomes Briarcliff Rd. The portion of Highway 42 from the I-285 interchange to Ponce is part of the National Highway System, a system of routes determined to be the most important for the nation’s mobility, economy and defense.

Another of my favorites is Ga. Highway 42. Highway 42 begins in Byron and end at its northern terminus in Brookhaven, a suburb of Atlanta. It sort of has a special place in my heart for several reasons. First, it runs concurrently with U.S. 23 through East Atlanta, where I was born. This stretch of road is known as Moreland Avenue, which the road is known as from Conley Rd. to Ponce de Leon Ave, after which it becomes Briarcliff Rd. The portion of Highway 42 from the I-285 interchange to Ponce is part of the National Highway System, a system of routes determined to be the most important for the nation’s mobility, economy and defense.

The second reason Highway 42 is special to me is because when we moved from Gresham Park to Rex in 1973, our house was right off of the highway. I thought my parents had moved us to Hooterville, but that’s another story altogether. Not long after we moved there, I pulled up to the stop sign at Double Bridge Road and Hwy 42 and the street sign for the highway was laying on the ground next to the stop sign. I took it home and put it on the wall of my room. It eventually made it downstairs to my father’s workshop and disappeared when the house was sold in 2015.

Highways 162 and 36 are great stretches of road for driving and 42 from Forsyth to Musella is a beautiful stretch of road. As far as North Georgia, Highway 53 stretches in an arc from Watkinsville, just outside of Athens to the Georgia-Alabama state line, just north of Cedartown. Georgia State Route 60 runs off of 53 in Dahlonega and goes through Suches and Morganton to the Tennessee Line. It is a beautiful ride through the Blue Ridge Mountains, but in places it is definitely not for the faint of heart!

The longest Georgia State Route is Highway 11. It is 376 miles long and runs the length of the state from north to south. Its southern terminus is the Florida state line below Statenville and the northern terminus is at the North Carolina line north of Blairsville.

I don’t really use GPS when planning a route on a back road. For one thing, I don’t really trust it because not all of the back roads are in the system, at least not in the way it wants you to go. I prefer to do it the old fashioned way, looking at a map, plotting a course and writing the route down. I will admit I have grown to depend on the dash map on the system, comparing my notes with the system’s map. And while technology is wonderful and GPS was a scientific breakthrough, I kind of miss the old days when you would get the U.S. Atlas from State Farm in the mail each year, or pick them up at gas stations along the way. To me, something has been lost in not being able to read and follow a map.

Okay, I will admit that sometimes I get turned around and have to backtrack. But, I’m lucky enough to have a pretty good sense of direction, so I’ve never wound up in West Nowhere when I was headed to East Jesus. At least not yet.